|

malcolm wright portfolio catalogues news & events the kiln contact us |

|

EXPECTATIONS AND RISK by Malcolm Wright Published in The Log Book issue 61, February 2015

By definition, woodfiring carries lots of risks. At the same time we all have expectations, or perhaps it is just hope. In working on sculpture I am taking on many risks: forms, cracks, temperature, atmosphere, slip application, etc. Maybe I am asking the clay to do things it doesn’t want to do. I use straight red brick clay (Lysella) from Georgia that withstands high temperature, but turns brown black when it gets too hot. I prefer the colour range available at cones 3, 4 and 5 - ochre and soft red at cone 3, with some dark colours at cone 5. In this temperature range some ash melts, but most does not. The kiln is a split bamboo shape, 6.4m (21 ft.) long, with a large preheat chamber and two and a half chambers for work. So far it has been fired 135 times to cone 10-14, and 10 times to cone 3-6. There can be a three-cone difference between the top front and the bottom back of each of the chambers, which are 1.8m (6 ft.) wide, by 1.5m (5 ft.) deep and 1.2m (4 ft.) high. As few shelves as possible are used for a brick clay firing, leaving the kiln two thirds empty to allow flyash to settle. I use only one layer of shelves across the front and two layers on posts across the back of each chamber, leaving space above the work.

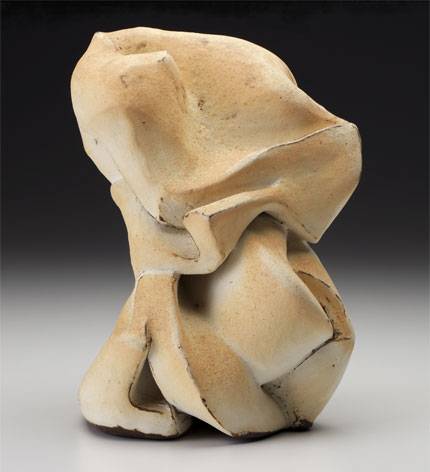

The foam sculptures created by John Chamberlain inspired me to make the crushed forms. My pod forms are inspired by the work of Jean Arp, as well as the question of how to join forms, making them integral to each other. The houses are derived from the light and shaddow patterns that I imagine passing through certain buildings by sculptor/architect Tony Smith.

In art speak today, intention is the buzz word. With my crushed pieces I start with no intention. In the morning I simply want to find out who I am today. I lay out the soft cut up pieces in front of me and pick them up one by one to see how they may fit together. The first joint is the most critical as it will make a structural corner. The second joint then gives structural integrity. From that point, the form tells me what to do with the remaining parts to bring it to resolution. Working this way with no intention gives me the freedom to explore form.

I apply some white slip to break out the form. and after many trials, have settled on a thin dip application. I wet the bisque form thoroughly and dip it in very thin white slip while being careful of errant drips. The area to be covered / not covered is planned carefully using large rubber bands to see what a suitable division in the form will look like, then I wax along the edge and remove the bands before applying the slip. I like the effect of the iron in the clay burning through the slip, so a thin application is important.

All the images (but one) shown here are of work from the September 2014 firing. The previous firing was on the hot side, more like cone 5-6 in front and the colours were very dark. There were almost no soft reds or ochres, so for this recent firing my plan was to lower the minimum temperature from cone 4 to cone 3.

There were at least three mistakes along the way. I lowered the temperature too much. The cones I could see were OK, but too much of the work in the body of the kiln was closer to cone 2, and had more oxidation than I intended. Next, I didn’t wet the bisque forms as much as before, or thin the slip enough. Thus the white is very strong and on the soft side, almost dusty, and no iron burned through the slip. Some of the slip even blistered and peeled. Finally, I had more cracks than before. I don’t mind interesting cracks, but I don’t like the ugly angular ones. Some of the forms were just too complex, and even though they were dried very slowly, ugly cracks distracted from the image.

About Expectations: much of the work from this firing came out different from that of previous firings, some much better, and some much worse than my expectation. But it could be that the kiln delivered something better than I expected. Perhaps the white under-fired oxidized result is better than my hope, and perhaps the over-fired black of the previous firing is better than I had thought. Perhaps it takes months and even years to see and understand your own work as it really is. Malcolm Wright received his BA from Marlboro College, Vermont, USA, and MFA from Corcoran School of Art George Washington University, Washington DC, in 1967. He lived in Kyoto and Karatsu, Japan from 1968-70, apprenticing at the Nakazato studio ‘Ochawangama’, before establishing the Turnpike Road Pottery, in Marlboro, VT in 1970. CONFERENCE PRESENTATION by Malcolm Wright NCECA Journal, Volume 9, #1, 1988 I spent about seven years under Japanese instruction: four years with Teruo Hara in Washington D.C. and studying in the storage collection of the Freer Gallery of Art, culminating in an M.F.A.; followed in 1967 by one year in Kyoto in a language school, also working as a production glazer in a small studio; then almost two years with the Nakazato family at Karatsu as an apprentice in their large and very famous studio. This was a very strong influence to either live up to or live down, but there were other strong influences prior to my Japanese experience, especially Abstract Expressionism in New York in the late 50s, as well as the powerful spaces in the medieval Italian hill towns, and my first introduction to Italian Futurism. In Karatsu, as a formal paid apprentice under the Nakazato family, six days a week I would line up with the other workers, bow, and promise to work that day as hard as I had the day before. I was expected to respond just as a Japanese apprentice would to every situation, and I did, except for one final moment. The eldest son asked me if I wanted to have an exhibition of my work before returning to the U.S. I said “yes” – the American response – because I knew that if I said “no” I would not be asked again for six months. The proper Japanese answer is to say “no” until the third time one is asked. I am very glad that I did respond most of the time as a Japanese, because I did eventually get to at least see or look into the inside thing. And what is that inside thing? It is not one big concept easily pointed to; it is the sum of many small details. In pottery, it is the sum of the texture and color of the microscopic particles of clay, and the size and the number of layers of bubbles in the glaze that produce the color, and the quality of light that is created in the relationship between the clay and glaze. It has to do with the shape of the lip as it fits in your mouth in relation to the color, texture, and taste of the food passing from the bowl to your mouth. Perhaps the inside thing that I brought from Japan is best explained in a poem written by Soji, a Chinese author on Shin Sai: Make nothing of the heart. Get off your dirty noisy thinking, make empty, don’t listen to your ear, listen by your heart, don’t listen by your heart, listen by Chi. we can just hear about things with the heart, we can feel only surface things. Chi is the inside thing. without thinking, to see the real thing. without thinking, the real thing comes from nothing. make nothing, is the Sai of the heart. way of thinking – without thinking. It was a propitious accident that I concluded my studies at Karatsu, because there I was able to study thousands of shards, in order to understand how to square or triangulate a round form, where and how to touch a bowl form in order to obtain a many sided form with a particular feeling. That’s it – a particular feeling is the most important element that I learned in Japan that American potters don’t particularly focus on. The word is aji in Japanese, translated it means “taste of a pot.” We would refer to it as perhaps the total effect of the pot’s texture, sound, color in relation to the food that is contained and eaten from that bowl. What is the feeling that results from that experience? The potter can put his or her feeling into the object so that the experience of the user is transported to more than just one level. It was in the Momoyama Period in Japan that the concept of function and beauty became one and not separate elements, and that brought Japanese pottery to its peak. The Japanese ceramic aesthetic is badly misunderstood in the U.S. both now and years ago. Before I went to Japan some of the popular words were badly overused, idealized and ultimately misunderstood. Just because there is some dirty brown wood ash on the side of a pot does not make the pot shibui. I am glad that wabi and sabi are no longer in popular use in this country. Anagama is another word that we don’t need to genuflect before – it only means “hole kiln.” Mr. Hamada advised me not to go and study with the Nakazato family because they were only tea potters, not folk potters. Here we can see the hierarchy of pottery groups in Japan. That is the same here and in Japan. Here we have art groups, the functional groups, the dinosaurs of the handmade groups, and the newly reinvented industrial groups. Mr. Hamada didn’t approve of the tea groups because they were only remnants of the past. He felt that I should study in the modem folk art group as they were the way to the future. But in the end, I felt that the tea potters, while stuck in the past, were interested in the spirit of the work itself, and that the folk groups were only shadows of Mr. Hamada and lacked the inside thing, the genius of Mr. Hamada himself. Japanese training did not nurture the creative self. In Japan the training was oriented to the technical base and to learning one thing at a time, not toward the visual understanding, not in decision making about form; much less content. Much of the training is rote learning, but their technical control makes much of our functional pottery look amateur. My forms have considerable relationship with Japanese forms. I remember writing a short piece about my work that concerned my being a traditional potter, even copying Japanese pots, but I am very aware of influences and I can see the Chinese, Korean, even English sources. Today I see much more of the Italian Futurists influence, but strongly modified by the Japanese approach to nature and function. I am very interested in chamber music. I believe that it is the ambiguity in the silence between two notes that give a performance life. I also believe that pottery is a performance medium,and that the interpretation of very fine details, both seen and intangible, are what gives a pot life. In working with the double wing extruded form I continue to find surprises in new combinations of the extruded parts. My interest years ago in the relationship between a circle and a square and in the geometry of Oribe pottery led me to extruded forms and the possibilities contained in one shape as the parts are altered and joined in endless different combinations. Inspired by a broken Oribe food container, wheel thrown and molded over a bisque form, my version of a similar pot was followed by a series of extruded forms, all based on the same double wing shape. My attitude about space is quit specific. I am interested in negative space and geometry, but not a rigid relationship of parts. It is the soft handling of the form that made the Oribe pottery come alive. Space is defined by light and light changes with time. I am also interested in space-time, the concept of understanding space from all perspectives simultaneously. My experience in the Italian hill towns taught me to look at forms, surfaces, volumes, and spaces from every perspective, including from deep in the earth, and all at the same time, much as the Cubists and Futurists did. Seigfreid Guideon, in his book Space, Time and Architecture, introduced this concept to me before Japan; Garth Clark reintroduced me to Futurism after my stay in Japan. While my wheel-thrown forms are classical Oriental forms in appearance, my approach is more conceptual. I tend to see them cut up in all directions at once in order to understand the pure geometry underlying each form as it evolves. At the same time, I feel my forms are softened by the Japanese attitude toward natural irregularity both in my treatment of details and in my use of glaze and wood firing. The shafts of light that pierce through the Italian hill towns, the strong shadows, windows, and the contrast between confined and unconfined space are clearly inspiration for my tall window vases. I see the vase as a torso or a kimono drape, and the window as a frame to look into or out of. Thus, “from the inside out,” has a cross current in the phrase. Another crossover came when I received about seventy very old Chinese pots from an uncle who had lived in China in the 20s. Having pots of this quality come into your home is a very powerful experience. The classicism of the Chinese forms certainly changed my attitude toward my own forms, moderating the more exuberant flower forms that preceded. “Culture shock” is a very valuable experience. It opens one’s eyes to one’s own culture. Like a liberal arts education, it helps us understand how little we know. In our town of eighty-thousand in Japan, we were the only foreigners. I think we really understood very little. It has to do with the unlearned learning we absorbed as children in the form of the Judeo-Christian tradition (I was born just west of Lake Woebegone) in contrast to the Confucian tradition that the Japanese child absorbs. I think that I am a foreigner in Japan and I am also a foreigner in this country, but the analytical Westerner is still the dominant force in me. CERAMIC PILLOWS by Malcolm Wright Published in The Studio Potter, Vol11 No1, December 1982 click on image below to view pdf.

Malcolm Wright is a potter who has used a wood burning kiln in Marlboro, Vermont since 1970. |

||

| home | contact us | malcolm wright | portfolio | news & events | kiln | catalogues | glaze formulas |

copyright © 2024 turnpike road pottery site design: eismontdesign